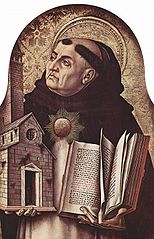

The Summa Theologica by Saint Thomas Aquinas

OF CONCUPISCENCE (FOUR ARTICLES)

We have now to consider concupiscence: under which head there are four points of inquiry:

(1) Whether concupiscence is in the sensitive appetite only?

(2) Whether concupiscence is a specific passion?

(3) Whether some concupiscences are natural, and some not natural?

(4) Whether concupiscence is infinite?

Whether concupiscence is in the sensitive appetite only?

Objection 1: It would seem that concupiscence is not only in the sensitive appetite. For there is a concupiscence of wisdom, according to Wis. 6:21: “The concupiscence [Douay: ‘desire’] of wisdom bringeth to the everlasting kingdom.” But the sensitive appetite can have no tendency to wisdom. Therefore concupiscence is not only in the sensitive appetite.

Objection 2: Further, the desire for the commandments of God is not in the sensitive appetite: in fact the Apostle says (Rom. 7:18): “There dwelleth not in me, that is to say, in my flesh, that which is good.” But desire for God’s commandments is an act of concupiscence, according to Ps. 118:20: “My soul hath coveted [concupivit] to long for thy justifications.” Therefore concupiscence is not only in the sensitive appetite.

Objection 3: Further, to each power, its proper good is a matter of concupiscence. Therefore concupiscence is in each power of the soul, and not only in the sensitive appetite.

On the contrary, Damascene says (De Fide Orth. ii, 12) that “the irrational part which is subject and amenable to reason, is divided into the faculties of concupiscence and anger. This is the irrational part of the soul, passive and appetitive.” Therefore concupiscence is in the sensitive appetite.

I answer that, As the Philosopher says (Rhet. i, 11), “concupiscence is a craving for that which is pleasant.” Now pleasure is twofold, as we shall state later on ([1252]Q[31], AA[3],4): one is in the intelligible good, which is the good of reason; the other is in good perceptible to the senses. The former pleasure seems to belong to soul alone: whereas the latter belongs to both soul and body: because the sense is a power seated in a bodily organ: wherefore sensible good is the good of the whole composite. Now concupiscence seems to be the craving for this latter pleasure, since it belongs to the united soul and body, as is implied by the Latin word “concupiscentia.” Therefore, properly speaking, concupiscence is in the sensitive appetite, and in the concupiscible faculty, which takes its name from it.

Reply to Objection 1: The craving for wisdom, or other spiritual goods, is sometimes called concupiscence; either by reason of a certain likeness; or on account of the craving in the higher part of the soul being so vehement that it overflows into the lower appetite, so that the latter also, in its own way, tends to the spiritual good, following the lead of the higher appetite, the result being that the body itself renders its service in spiritual matters, according to Ps. 83:3: “My heart and my flesh have rejoiced in the living God.”

Reply to Objection 2: Properly speaking, desire may be not only in the lower, but also in the higher appetite. For it does not imply fellowship in craving, as concupiscence does; but simply movement towards the thing desired.

Reply to Objection 3: It belongs to each power of the soul to seek its proper good by the natural appetite, which does not arise from apprehension. But the craving for good, by the animal appetite, which arises from apprehension, belongs to the appetitive power alone. And to crave a thing under the aspect of something delightful to the senses, wherein concupiscence properly consists, belongs to the concupiscible power.

Whether concupiscence is a specific passion?

Objection 1: It would seem that concupiscence is not a specific passion of the concupiscible power. For passions are distinguished by their objects. But the object of the concupiscible power is something delightful to the senses; and this is also the object of concupiscence, as the Philosopher declares (Rhet. i, 11). Therefore concupiscence is not a specific passion of the concupiscible faculty.

Objection 2: Further, Augustine says (QQ. 83, qu. 33) that “covetousness is the love of transitory things”: so that it is not distinct from love. But all specific passions are distinct from one another. Therefore concupiscence is not a specific passion in the concupiscible faculty.

Objection 3: Further, to each passion of the concupiscible faculty there is a specific contrary passion in that faculty, as stated above ([1253]Q[23], A[4]). But no specific passion of the concupiscible faculty is contrary to concupiscence. For Damascene says (De Fide Orth. ii, 12) that “good when desired gives rise to concupiscence; when present, it gives joy: in like manner, the evil we apprehend makes us fear, the evil that is present makes us sad”: from which we gather that as sadness is contrary to joy, so is fear contrary to concupiscence. But fear is not in the concupiscible, but in the irascible part. Therefore concupiscence is not a specific passion of the concupiscible faculty.

On the contrary, Concupiscence is caused by love, and tends to pleasure, both of which are passions of the concupiscible faculty. Hence it is distinguished from the other concupiscible passions, as a specific passion.

I answer that, As stated above [1254](A[1]; Q[23], A[1]), the good which gives pleasure to the senses is the common object of the concupiscible faculty. Hence the various concupiscible passions are distinguished according to the differences of that good. Now the diversity of this object can arise from the very nature of the object, or from a diversity in its active power. The diversity, derived from the nature of the active object, causes a material difference of passions: while the difference in regard to its active power causes a formal diversity of passions, in respect of which the passions differ specifically.

Now the nature of the motive power of the end or of the good, differs according as it is really present, or absent: because, according as it is present, it causes the faculty to find rest in it; whereas, according as it is absent, it causes the faculty to be moved towards it. Wherefore the object of sensible pleasure causes love, inasmuch as, so to speak, it attunes and conforms the appetite to itself; it causes concupiscence, inasmuch as, when absent, it draws the faculty to itself; and it causes pleasure, inasmuch as, when present, it makes the faculty to find rest in itself. Accordingly, concupiscence is a passion differing “in species” from both love and pleasure. But concupiscences of this or that pleasurable object differ “in number.”

Reply to Objection 1: Pleasurable good is the object of concupiscence, not absolutely, but considered as absent: just as the sensible, considered as past, is the object of memory. For these particular conditions diversify the species of passions, and even of the powers of the sensitive part, which regards particular things.

Reply to Objection 2: In the passage quoted we have causal, not essential predication: for covetousness is not essentially love, but an effect of love. We may also say that Augustine is taking covetousness in a wide sense, for any movement of the appetite in respect of good to come: so that it includes both love and hope.

Reply to Objection 3: The passion which is directly contrary to concupiscence has no name, and stands in relation to evil, as concupiscence in regard to good. But since, like fear, it regards the absent evil; sometimes it goes by the name of fear, just as hope is sometimes called covetousness. For a small good or evil is reckoned as though it were nothing: and consequently every movement of the appetite in future good or evil is called hope or fear, which regard good and evil as arduous.

Whether some concupiscences are natural, and some not natural?

Objection 1: It would seem that concupiscences are not divided into those which are natural and those which are not. For concupiscence belongs to the animal appetite, as stated above (A[1], ad 3). But the natural appetite is contrasted with the animal appetite. Therefore no concupiscence is natural.

Objection 2: Further, material differences makes no difference of species, but only numerical difference; a difference which is outside the purview of science. But if some concupiscences are natural, and some not, they differ only in respect of their objects; which amounts to a material difference, which is one of number only. Therefore concupiscences should not be divided into those that are natural and those that are not.

Objection 3: Further, reason is contrasted with nature, as stated in Phys. ii, 5. If therefore in man there is a concupiscence which is not natural, it must needs be rational. But this is impossible: because, since concupiscence is a passion, it belongs to the sensitive appetite, and not to the will, which is the rational appetite. Therefore there are no concupiscences which are not natural.

On the contrary, The Philosopher (Ethic. iii, 11 and Rhetor. i, 11) distinguishes natural concupiscences from those that are not natural.

I answer that, As stated above [1255](A[1]), concupiscence is the craving for pleasurable good. Now a thing is pleasurable in two ways. First, because it is suitable to the nature of the animal; for example, food, drink, and the like: and concupiscence of such pleasurable things is said to be natural. Secondly, a thing is pleasurable because it is apprehended as suitable to the animal: as when one apprehends something as good and suitable, and consequently takes pleasure in it: and concupiscence of such pleasurable things is said to be not natural, and is more wont to be called “cupidity.”

Accordingly concupiscences of the first kind, or natural concupiscences, are common to men and other animals: because to both is there something suitable and pleasurable according to nature: and in these all men agree; wherefore the Philosopher (Ethic. iii, 11) calls them “common” and “necessary.” But concupiscences of the second kind are proper to men, to whom it is proper to devise something as good and suitable, beyond that which nature requires. Hence the Philosopher says (Rhet. i, 11) that the former concupiscences are “irrational,” but the latter, “rational.” And because different men reason differently, therefore the latter are also called (Ethic. iii, 11) “peculiar and acquired,” i.e. in addition to those that are natural.

Reply to Objection 1: The same thing that is the object of the natural appetite, may be the object of the animal appetite, once it is apprehended. And in this way there may be an animal concupiscence of food, drink, and the like, which are objects of the natural appetite.

Reply to Objection 2: The difference between those concupiscences that are natural and those that are not, is not merely a material difference; it is also, in a way, formal, in so far as it arises from a difference in the active object. Now the object of the appetite is the apprehended good. Hence diversity of the active object follows from diversity of apprehension: according as a thing is apprehended as suitable, either by absolute apprehension, whence arise natural concupiscences, which the Philosopher calls “irrational” (Rhet. i, 11); or by apprehension together with deliberation, whence arise those concupiscences that are not natural, and which for this very reason the Philosopher calls “rational” (Rhet. i, 11).

Reply to Objection 3: Man has not only universal reason, pertaining to the intellectual faculty; but also particular reason pertaining to the sensitive faculty, as stated in the [1256]FP, Q[78], A[4]; [1257]FP, Q[81], A[3]: so that even rational concupiscence may pertain to the sensitive appetite. Moreover the sensitive appetite can be moved by the universal reason also, through the medium of the particular imagination.

Whether concupiscence is infinite?

Objection 1: It would seem that concupiscence is not infinite. For the object of concupiscence is good, which has the aspect of an end. But where there is infinity there is no end (Metaph. ii, 2). Therefore concupiscence cannot be infinite.

Objection 2: Further, concupiscence is of the fitting good, since it proceeds from love. But the infinite is without proportion, and therefore unfitting. Therefore concupiscence cannot be infinite.

Objection 3: Further, there is no passing through infinite things: and thus there is no reaching an ultimate term in them. But the subject of concupiscence is not delighted until he attain the ultimate term. Therefore, if concupiscence were infinite, no delight would ever ensue.

On the contrary, The Philosopher says (Polit. i, 3) that “since concupiscence is infinite, men desire an infinite number of things.”

I answer that, As stated above [1258](A[3]), concupiscence is twofold; one is natural, the other is not natural. Natural concupiscence cannot be actually infinite: because it is of that which nature requires; and nature ever tends to something finite and fixed. Hence man never desires infinite meat, or infinite drink. But just as in nature there is potential successive infinity, so can this kind of concupiscence be infinite successively; so that, for instance, after getting food, a man may desire food yet again; and so of anything else that nature requires: because these bodily goods, when obtained, do not last for ever, but fail. Hence Our Lord said to the woman of Samaria (Jn. 4:13): “Whosever drinketh of this water, shall thirst again.”

But non-natural concupiscence is altogether infinite. Because, as stated above [1259](A[3]), it follows from the reason, and it belongs to the reason to proceed to infinity. Hence he that desires riches, may desire to be rich, not up to a certain limit, but to be simply as rich as possible.

Another reason may be assigned, according to the Philosopher (Polit. i, 3), why a certain concupiscence is finite, and another infinite. Because concupiscence of the end is always infinite: since the end is desired for its own sake, e.g. health: and thus greater health is more desired, and so on to infinity; just as, if a white thing of itself dilates the sight, that which is more white dilates yet more. On the other hand, concupiscence of the means is not infinite, because the concupiscence of the means is in suitable proportion to the end. Consequently those who place their end in riches have an infinite concupiscence of riches; whereas those who desire riches, on account of the necessities of life, desire a finite measure of riches, sufficient for the necessities of life, as the Philosopher says (Polit. i, 3). The same applies to the concupiscence of any other things.

Reply to Objection 1: Every object of concupiscence is taken as something finite: either because it is finite in reality, as being once actually desired; or because it is finite as apprehended. For it cannot be apprehended as infinite, since the infinite is that “from which, however much we may take, there always remains something to be taken” (Phys. iii, 6).

Reply to Objection 2: The reason is possessed of infinite power, in a certain sense, in so far as it can consider a thing infinitely, as appears in the addition of numbers and lines. Consequently, the infinite, taken in a certain way, is proportionate to reason. In fact the universal which the reason apprehends, is infinite in a sense, inasmuch as it contains potentially an infinite number of singulars.

Reply to Objection 3: In order that a man be delighted, there is no need for him to realize all that he desires: for he delights in the realization of each object of his concupiscence.

Copyright ©1999-2023 Wildfire Fellowship, Inc all rights reserved

Keep Site Running

Keep Site Running