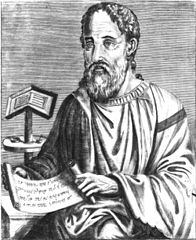

An Ecclesiastical History To The 20th Year Of The Reign Of Constantine by Eusebius

LIFE OF EUSEBIUS PAMPHILUS BY VALESIUS

ACCORDING to the testimony of Socrates, a book relative to the life of Eusebius was written by Acacius, his scholar and successor in the see of Cæsarea. But since this book, through that negligence in antiquity to which the loss of many others is to be ascribed, is not now extant, we will endeavour, from the testimonies of the several writers who have mentioned Eusebius, to supply the defect.

It appears that Eusebius was born in Palestine, about the close of the reign of Gallienus, one proof of which is, that by the ancients, particularly by Basilius and Theodoret, he is frequently termed a Palestinian. It is possible, indeed, that he might have received that name from his being the bishop of Cæsarea, yet probability is in favour of his having derived it from his country; certainly he himself affirms, that when a youth, he was educated and dwelt in Palestine, and that there he first saw Constantine, when journeying through it with Diocletian Augustus; and after repeating the contents of a law, written in favour of the Christians, by Constantine to the Palestinians, he observes, “This letter of the Emperor’s is the first sent to us.”

On the authority of Eusebius himself, it may be affirmed, that he was born in the last part of the reign of Gallienus, 259 A.D.; for, in his Ecclesiastical History, he informs us, that Dionysius, bishop of Alexandria, lived in his own age.| Therefore, since Dionysius died in the twelfth year of the reign of Gallienus, Eusebius must have been born before, if he lived within the time of that prelate. The same also follows, from his stating,* that Paul of Samosata had revived the heresy of Artemon, in his† age. And in his history of the occurrences during the reign of Gallienus, before he begins the narrative of the error and condemnation of Paul of Samosata, he observes, “but now, after the history of these things, we will transmit to posterity an account of our own times.”

Respecting his parents we know nothing, except that Nicephorus Callistus, by what authority we cannot say, speaks of his mother as the sister of Pamphilus the martyr. In Arius’s letter, he is termed brother to Eusebius of Nicomedia. Though he possibly might, on account of his friendship, have received this appellation, yet it is more probable that he was nearly related to the Nicomedian bishop; especially since he of Cæsarea only, though many others there are mentioned, is termed by Arius, brother to that prelate. Besides, the Nicomedian Eusebius was a native of Syria, and bishop first of Berytus: nor was it then the usage, that foreigners and persons unknown should be promoted to the government of churches.

Neither is it known what teachers he had in secular learning; but in sacred literature, he had for his preceptor Dorotheus, the eunuch, presbyter of the Antiochian church, of whom he makes honourable mention in his Seventh Book. Notwithstanding Eusebius there says only, that he had heard Dorotheus expounding the Holy Scriptures with propriety, in the Antiochian church, we are not inclined to object to any one thence inferring, with Trithemius, that Eusebius was Dorotheus’s disciple. Theotecnus being at that time dead, the bishopric of the church of Cæsarea was administered by Agapius, a person of eminent piety and great liberality to the poor. By him Eusebius was admitted into the clerical office, and with Pamphilus, a presbyter of distinction at that time in the Cæarean church, he entered into the firmest friendship. Pamphilus was, as Photius relates, a Phœnician, born at Berytus, and scholar of Pierius, a presbyter of the Alexandrian church; who, since he was animated with the most singular attachment to sacred literature, and was with the utmost zeal collecting all the works of the ecclesiastical writers, especially Origen, founded a very celebrated school and library at Cæsarea, of which school Eusebius seems to have been the first master. Indeed, it is affirmed, by Eusebius, that Apphianus, who suffered martyrdom in the third year of the persecution, had been instructed by him in the sacred Scriptures, in the city of Cæsarea. From that time Eusebius’s intimacy with Pamphilus was so great, and such was his attention to him, as his inseparable companion till death, that he acquired the name of Pamphilus. And not only while the latter was living, but after his death, Eusebius cherished toward him the greatest affection, and ever spoke of him with reverence and tenderness. This is exemplified in the three books written by Eusebius, concerning the life of Pamphilus, eulogized by St. Jerome, and by many passages in his Ecclesiastical History, and in his account of the martyrs of Palestine. In his Second Book, also, against Sabellius, written by Eusebius, after the Nicene Council, he frequently commends Pamphilus, though he suppresses his name. In the commencement of that discourse, Eusebius observes, “I think that my ears are as yet affected by the remembrance of that blessed man, who spake with so much piety, and yours still retain the sound of his voice; for I seem to be yet hearing him utter that devout word, ‘the only begotten Son of God,’ a phrase he constantly employed: for it was the remembrance of the only begotten to the glory of the unborn Father. Now we have heard the apostle commanding that presbyters ought to be honoured with a double honour, those especially who have laboured in the word and doctrine.” And he thus again speaks of his friend: “With these reminiscences of that blessed man I am not elated, but wish I could so speak, as if, together with you, I were always hearing from him. And the words now cited may be pleasing to him, for it is the glory of good servants to speak truth concerning the Lord, and it is the honor of those lathers, who have taught well, if their doctrines be repeated.” Some “may insinuate, that these were phrases, the creatures of his lips, and no proof of the feelings of his heart; but I remember, in what a satisfactory manner, I have heard with you, his solemn asseveration, that there was not one thing on his tongue and another in his heart.” Shortly after, he says: “But now on account of the memory and honour of this our father, so good, so laborious, and so vigilant for the church, let these facts be briefly stated by us. For we have not mentioned yet his family, his education or learning, nor narrated the other incidents of his life, and its leading or principal object.” These passages in Eusebius were pointed out to us by the most learned Franciscus Ogerius. Hence it may be satisfactorily inferred, that it was not any family alliance, but the bond of amity that connected Eusebius with Pamphilus. Eusebius, though he mentions Pamphilus so frequently, and boasts so highly of his friendship, yet never speaks of him as a relative. The testimony of Eusebius alone is sufficient to decide that Pamphilus, though his friend, was not his kinsman. Since in the close of his Seventh Book of Ecclesiastical History, where he is making mention of Agapius, bishop of Cæsarea, he says: “In his time, we became acquainted with Pamphilus, a most eloquent man, and in his life and practices truly a philosopher, and in the same church, ennobled with the honor of the presbytery.” Since Eusebius attests that Pamphilus was then first known to him, it is sufficiently evident, that family alliance was not the tie that connected them.

In these times occurred that most severe persecution of the Christians, which was begun by Diocletian, and continued by the following emperors for ten years. During this persecution, Eusebius, at that time being a presbyter of the church of Cæsarea, remained almost constantly in that city, and by continual exhortations, prepared many for martyrdom; amongst whom was Apphianus, a noble youth, whose illustrious fortitude is related in Eusebius’s book concerning the martyrs of Palestine. In the same year Pamphilus was cast into prison, where he spent two whole years in bonds, during which time, Eusebius by no means deserted his friend and companion, but visited him continually, and in the prison wrote, together with him, five books in defence of Origen; but the sixth and last book of that work, he finished after the death of Pamphilus.—That whole work was by Eusebius and Pamphilus dedicated to Christian confessors, living in the mines of Palestine. In the time of this persecution, on account, probably, of some urgent affairs of the church, Eusebius went to Tyre, in which city he witnessed the glorious martyrdom of five Egyptian Christians; and afterwards, on his arrival in Egypt and Thebais, the persecution then prevailing there, he beheld the admirable constancy of many martyrs of both sexes. Some have insinuated that Eusebius, to exempt himself in this persecution, from imprisonment, sacrificed to idols; and that this was objected against him, as will be hereafter related, by the Egyptian bishops and confessors, in the synod at Tyre. But we doubt not that this is false, and that it was a calumny forged by the enemies of Eusebius. For had a crime so great been really committed by him, how could he have been afterwards appointed bishop of Cæsarea? How is it likely that he should, in this case, have been invited by the Antiochians to undertake the episcopate of their city? And yet Cardinal Baronius has seized on that as certain and undoubted, which by his enemies, for litigious purposes, was objected against Eusebius, but never confirmed by the testimony of any one. At the same time, a book was written by Eusebius against Hierocles. For Hierocles of Nicomedia, about the beginning of the persecution, when the Christian Churches were every where harassed, published, in the city of Nicomedia, as an insult to a religion then assailed by all its enemies, two books against the Christian faith; in which books he asserted, that Apollonius Tyaneus performed more and greater things than Christ. But Eusebius disregarding the man, confuted him in a very short volume.

Agapius, bishop of Cæsarea during this interval, being dead, the persecution subsiding, and peace being restored to the church, Eusebius, by common consent, succeeded to the episcopal dignity at Cæsarea. Others represent Agricola, who subscribed to the synod of Ancyra, at which he was present in the 314th year of the Christian era, to be the successor of Agapius. This is affirmed by Baronius in his Annals, and Blondellus. The latter writes, that Eusebius undertook the administration of the church of Cæsarea, after the death of Agricola, about the year 315. But these subscriptions of the bishops, extant only in the Latin collections of the canons, seem in our judgment to be entitled to little credit. For they occur neither in the Greek copies, nor in the Latin Versions of Dionysius Exiguns. Besides, Eusebius,| enumerating the bishops of the principal dioceses, where the persecution began and raged, ends with the mention of Agapius, bishop of Cæsarea; who, he observes, laboured much, during that persecution, for the good of his own church. The necessary inference, therefore, is, that Agapius must have been bishop until the end of the persecution. But Eusebius was elevated to the episcopal office immediately after that persecution; for after peace was restored to the church, Eusebius* and other prelates being invited by Paulinus bishop of Tyre, to the dedication of a cathedral, Eusebius made there a very eloquent oration. Now this happened before the rebellion of Licinius against Constantine, in the 315th year of the Christian era, about which period Eusebius wrote those celebrated books, “De Demonstratione Evangelicâ,” and “De Præparatione Evangelicâ.” And these books were certainly written before the Nicene Synod, since they are expressly mentioned in his Ecclesiastical History, which was written before that council.

Meanwhile, Licinius, who managed the government in the eastern empire, excited by sudden rage, began to persecute the Christians, especially the prelates, whom he suspected of showing more regard, and of offering up more prayers for Constantine than for himself. Constantine, however, having defeated him in two battles by land and sea, compelled him to surrender, and restored peace to the Christians of the east.

A disturbance, however, far more grievous, arose at that time, amongst the Christians themselves. Arius, a presbyter of the city of Alexandria, publicly advanced some new and impious tenets relative to the Son of God, and persisting in this, notwithstanding repeated admonition by Alexander the bishop, he and his associates in this heresy, were at length expelled. Highly resenting this, Arius sent letters with a statement of his own faith to all the bishops of the neighbouring cities, in which he complained, that though he asserted the same doctrines which the rest of the eastern prelates maintained, he had been unjustly deposed by Alexander. Many bishops, imposed on by these artifices, and powerfully excited by Eusebius of Nicomedia, who openly favoured the Arian party, wrote letters in defence of Arius to Alexander bishop of Alexandria, entreating him to restore Arius to his former rank in the church. Our Eusebius was one of their number, whose letter, written to Alexander, is extant in the acts of the seventh Œeumenical Synod. The example of Eusebius of Cæsarea was soon followed by Theodotius and Paulinus, the one bishop of Laodicea, the other of Tyre, who interceded with Alexander for Arius’s restoration. Since Arius boasted on every occasion of this letter, and by the authority of such eminent men, drew many into the participation of his heresy, Alexander was compelled to write to the other eastern bishops, showing the justice of the expulsion of Arius. Two letters of Alexander’s are yet extant; the one to Alexander, bishop of Constantinople, in which the former complains of three Syrian bishops, who agreeing with Arius, had more than ever inflamed that contest, which they ought rather to have suppressed. These three, as may be learned from Arius’s letter to Eusebius, bishop of Nicomedia, are Eusebius, Theodotius, and Paulinus. The other letter of Alexander’s, written to all the bishops throughout the world, Socrates records in his first book. To these letters of Alexander’s, almost all the eastern bishops subscribed, amongst whom the most eminent were Philogonius, bishop of Antioch, Eustathius of Beræa, and Macarius of Jerusalem.

The bishops who favoured the Arian party, especially Eusebius of Nicomedia, imagining themselves to be severely treated in Alexander’s letters, became much more vehement in their defence of Arius. For our Eusebius of Cæsarea, together with Patrophilus, Paulinus, and other Syrian bishops, merely voted that it should be lawful for Arius, as a presbyter, to hold assemblies in his church; at the same time, that he should be subject to Alexander, and seek from him reconciliation and communion. The bishops disagreeing thus among themselves, some favouring the party of Alexander, and others that of Arius; the contest became singularly aggravated. To remedy this, Constantine, from all parts of the Roman world, summoned to Nicea, a city of Bithynia, a general synod of bishops, such as no age before had seen. In this greatest and most celebrated council, our Eusebius was far from an unimportant person. For he both had the first seat on the right hand, and in the name of the whole synod addressed the emperor Constantine, who sat on a golden chair, between the two rows of the opposite parties. This is affirmed by Eusebius himself in his Life of Constantine, and by Sozomen in his Ecclesiastical History. Afterwards, when there was a considerable contest amongst the bishops, relative to a creed or form of faith, our Eusebius proposed a formula, at once simple and orthodox, which received the general commendation both of the bishops and of the emperor himself. Something, notwithstanding, seeming to be wanting in the creed, to confute the impiety of the new opinion, the fathers of the Nicene Council determined that these words, “VERY GOD OF VERY GOD, BEGOTTEN NOT MADE, BEING OF ONE SUBSTANCE WITH THE FATHER,” should be added. They also annexed anathemas against those who should assert that the Son of God was made of things not existing, and that there was a time when he was not. At first, indeed, our Eusebius refused to admit the word “consubstantial,” but when the import of that word was explained to him by the other bishops, he consented, and as he himself relates in his letter to his diocese at Cæsarea, subscribed to the creed. Some affirm that it was the necessity of circumstances, or the fear of the emperor, and not the conviction of his own mind, that induced Eusebius to subscribe to the Nicene Council. Of some, present at the synod, this might be believed, but this we cannot think of Eusebius, bishop of Cæsarea. After the Nicene Council, too, Eusebius always condemned| those who asserted that the Son of God was made of things not existing. Athanasius likewise affirms the same concerning him, who though he frequently mentions that Eusebius subscribed to the Nicene Council, nowhere intimates that he did it insincerely. Had Eusebius subscribed to that Council, not according to his own mind, but fraudulently and in pretence, why did he afterwards send the letter we have mentioned to his diocese at Cæsarea, and there in ingenuously profess that he had embraced that faith which had been published in the Nicene Council?

After that Council, the Arians, through fear of the emperor, were for a short time quiet. But at length, confidence being resumed, they ingratiated themselves into the favour of the prince, and began, by every method and device, to persecute the Catholic prelates. Their first attack fell on Eustathius, bishop of the city of Antioch, who was eminent for the glory of his confession, and was chief amongst the advocates of the Nicene faith. Eustathius was, therefore, accused before the emperor of maintaining the Sabellian impiety, and of slandering Helena Augusta, the emperor’s mother. A numerous assembly of bishops was convened in the city of Antioch, in which Eusebius of Nicomedia, the chief and ringleader of the whole faction, presided. In addition to the accusation advanced at this assembly by Cyrus, bishop of the Beræans, against Eustathius, of maintaining the impious doctrine of Sabellius, another was devised against him of incontinency, and he was therefore expelled from his diocese. On this account, a very impetuous tumult arose at Antioch. The people, divided into two factions, the one requesting that the episcopacy of the Antiochian church might be conferred on Eusebius of Cæsarea, the other, that Eustathius their bishop might be restored, would have resorted to measures of violence, had not the fear and authority of the emperor and judges prevented it. The sedition being at length subdued, and Eustathius banished, our Eusebius, though entreated both by the people, and the bishops that were present, to undertake the administration of the church at Antioch, nevertheless refused. And when the bishops, by letters written to Constantine, had acquainted him with their own vote, and with the suffrages of the people, Eusebius wrote his letters also to that prince, who highly commended his resolution.

Eustathius having been in this manner deposed, in the year 330, the Arians turned the violence of their fury on Athanasius; and in the prince’s presence they complained first of his ordination; secondly, that he had exacted the impost of a linen garment from the provincials; thirdly, that he had broken a sacred cup; and lastly, that he had murdered one Arsenius, a bishop. Constantine, wearied with these vexatious litigations, appointed a council in the city of Tyre, and directed Athanasius the bishop to proceed there, to have his cause tried. In that Synod, Eusebius bishop of Cæsarea, whom Constantine had desired should be present, sat amongst others, as judge. Potamo, bishop of Heracleopolis, who had come with Athanasius the bishop and some Egyptian prelates, seeing him sitting in the council, is said to have addressed him in these words: “Is it fit, Eusebius, that you should sit, and that the innocent Athanasius should stand to be judged by you? Who can endure this? Were you not in custody with me, during the time of the persecution? And I truly, in defence of the truth, lost an eye; but you are injured in no part of your body, neither did you undergo martyrdom, but are alive and whole. In what manner did you escape out of prison, unless you promised to our persecutors that you would commit the detestable thing? And perhaps you have done it.” This is related by Epiphanius, in the heresy of the Meletians. Hence it appears, that they are mistaken who affirm, that Eusebius had sacrificed to idols, and that he had been convicted of the fact in the Tyrian synod. For Potamo did not attest that Eusebius had sacrificed to idols, but only that, being dismissed from prison safe and well, it afforded ground of suspicion. It was, however, evidently possible that Eusebius might have been liberated from confinement in a manner very different from that of Potamo’s insinuation. From the words of Epiphanius, it seems to be inferred that Eusebius bishop of Cæsarea, presided at this synod; for he adds, that Eusebius, being previously affected in hearing the accusation against him by Potamo, dismissed the council. Yet by other writers we are informed, that not Eusebius bishop of Cæsarea, but Eusebius of Nicomedia, presided at the Tyrian synod.

After that council, all the bishops who had assembled at Tyre, repaired, by the emperor’s orders, to Jerusalem, to celebrate the consecration of the great church, which Constantine in honour of Christ had erected in that place. There our Eusebius graced the solemnity, by the several sermons he delivered. And when the emperor, by very strict letters, had summoned the bishops to his own court, that in his presence they might give an account of their fraudulent and litigious conduct towards Athanasius, our Eusebius, with five others, went to Constantinople, and furnished that prince with a statement of the whole transaction. Here also, in the palace, he delivered his tricennalian oration, which the emperor heard with the utmost joy, not so much on account of any praises to himself, as on account of the praises of God, celebrated by Eusebius throughout the whole of that oration. This oration was the second delivered by Eusebius in that palace. For he had before made an oration there, concerning the sepulchre of our Lord, which the emperor heard standing; nor could he, though repeatedly entreated by Eusebius, be persuaded to sit in the chair placed for him, alleging that it was fit that discourses concerning God should be heard in that posture.

How dear and acceptable our Eusebius was to Constantine, may be known both from the facts we have narrated, as well as from many other circumstances. For he both received many letters from him, as may be seen in the books already mentioned, and was not unfrequently sent for to the palace, where he was entertained at table, and honoured with familiar conversation. Constantine, moreover, related to our Eusebius, the vision of the cross seen by him when on his expedition against Maxentius; and showed to him, as Eusebius informs us, the labarum that he had ordered to be made to represent the likeness of that cross. Constantine also committed to Eusebius, since he knew him to be most skilful in Biblical knowledge, the care and superintendence of transcribing copies| of the Scriptures, which he wanted for the accommodation of the churches he had built at Constantinople. Lastly, the book concerning the Feast of Easter, dedicated to him by our Eusebius, was a present to Constantine, so acceptable, that he ordered its immediate translation into Latin; and by letter entreated Eusebius, that he would communicate, as soon as possible, works of this nature, with which he was engaged, to those concerned in the study of sacred literature.

About the same time, Eusebius dedicated a small book to the emperor Constantine, in which was comprised his description of the Jerusalem church, and of the gifts that had been consecrated there,—which book, together with his tricennalian oration, he placed at the close of his Marcellus; of which the last three, “De Ecclesiasticâ Theologiâ,” he dedicated to Flaccillus, bishop of Antioch. Flaccillus entered on that bishopric, a little before the synod of Tyre, which was convened in the consulate of Constantius and Albinus, A.D. 335. It is certain that Eusebius, in his First Book writes in express words, that Marcellus had been deservedly condemned by the church. Now Marcellus was first condemned in the synod held at Constantinople, by those very bishops that had consecrated Constantine’s church at Jerusalem, in the year of Christ 335, or, according to Baronius, 336. Socrates, indeed, acknowledges only three books written by Eusebius against Marcellus, namely those entitled, “De Ecclesiasticâ Theologiâ;” but the whole work by Eusebius, against Marcellus, comprised Five Books. The last books written by Eusebius, seem to be the four on the life of Constantine; for they were written after the death of that emperor, whom Eusebius did not long survive. He died about the beginning of the reign of Constantius Augustus, a little before the death of Constantine the Younger, which happened, according to the testimony of Socrates’ Second Book, when Acindynus and Proculus were consuls, A.D. 340.

We cannot admit, what Scaliger has affirmed, that Eusebius’s books against Porphyry, were written under Constantius, the son of Constantine the Great, especially since this is confirmed by the testimony of no ancient writer. Besides, in what is immediately after asserted by Scaliger, that Eusebius wrote his last three| books of the “Evangelic Demonstration,” against Porphyry, there is an evident error. St. Jerome says, indeed, that Eusebius in three volumes, (that is, in the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth,) answered Porphyry, who in the Twelfth and Thirteenth of those books which he published against the Christians, had attempted to confute the book of the prophet Daniel. St. Jerome,* however, does not mean, as Scaliger thought, Eusebius’s Books on Evangelic Demonstration, but the books he wrote against Porphyry, entitled, according to Photius’s Bibliotheca, ἐλέγχου καὶ ἀπολογίας, Refutation and Defence. We are also persuaded that Eusebius wrote these books after his Ecclesiastical History; because Eusebius, in the Sixth Book† of his Ecclesiastical History, where he quotes a notorious passage from Porphyry,‡ makes no allusion to any books he had written against him, though he is always sufficiently careful to quote his own works, and thereupon refers the reader to the study of them.

We avail ourselves of the present opportunity to make some remarks relative to Eusebius’s Ecclesiastical History, the chief subject of our present labour and exertions. Much, indeed, had been written by our Eusebius, both against Jews and Heathens, to the edification of the orthodox and general church, and in confirmation of the verity of the Christian faith: nevertheless, amongst all his books, his Ecclesiastical History deservedly stands pre-eminent. For before Eusebius, many had written in defence of Christianity, and had, by the most satisfactory arguments, refuted the Jews on the one hand and the Heathens on the other, but not one, before Eusebius, had delivered to posterity a history of ecclesiastic affairs. On which account, therefore, because Eusebius not only was the first to show this example, but has transmitted to us what he undertook, in a state so complete and perfect, he is entitled to the greater commendation. Though many, it is true, induced by his example, have, since his time, furnished accounts of ecclesiastical affairs, yet they have not only uniformly commenced their histories from the times of Eusebius, but have left him to be the undisputed voucher of the period of which he yet remains the exclusive historian. And if any one be entitled to the epithet of the Father of Ecclesiastical History, it certainly belongs to him.

By what preliminary circumstances Eusebius was led to this undertaking, it is not difficult to conjecture. Having in his Chronological Canons accurately stated the time of the advent and passion of Jesus Christ, the names of the several bishops that had presided in the four principal churches, and of the eminent characters therein, and having also detailed an account of the successive heresies and persecutions, he was, as it were, led by insensible degrees to write an Ecclesiastical History, to furnish a full development of what had been but briefly sketched in his Chronological Canons. This, indeed, is expressly confirmed by Eusebius in his preface to that work; where he also implores the forbearance of the candid reader, if his work should be found less substantial, for he was the first who had devoted himself to the inquiry, and had to commence a path unbeaten by previous footsteps. Though this, it is true, in the view of some, may appear not so much an apology as an indirect device of acquiring praise.

Though it is evident, from Eusebius’s own testimony, that he wrote his Ecclesiastical History after his Chronological Canons, it is remarkable that the twentieth year of Constantine is a limit common to both those works. Nor is it less singular, that, though the Nicene Council was held in that year yet no mention is made of it in either work. But in his Chronicle, at the fifteenth year of Constantine, we read that “Alexander is ordained the nineteenth bishop of the Alexandrian church, by whom Arius the presbyter being expelled, associates many in his own impiety. A synod, therefore, of three hundred and eighteen bishops, convened at Nice, a city of Bithynia, by their agreement on the term ὁμοούσιος (consubstantial, or co-essential), suppressed all the devices of the heretics.” It is sufficiently evident that these words were not written by Eusebius, but by St. Jerome, who in Eusebius’s Chronicle inserted many passages of his own. For, not to mention that this reference to the Nicene Council is inserted in a place with which it has no proper connexion, who could believe that Eusebius would thus write concerning Arius, or should have inserted the term ὁμοούσιος in his own Chronicle; which word, as we shall hereafter state, was not satisfactory to him? Was it likely that Eusebius should, in the Chronicle, state that three hundred and eighteen bishops were present at the Nicene synod, and in his Third Book on the Life of Constantine, say expressly that something more than two hundred and fifty sat in that council? We have no doubt, however, that the Ecclesiastical History was not completely finished by Eusebius till some years after the council at Nice. But when Eusebius had determined, as he states in the beginning of his history, to close his narrative with that, era of peace which shone from heaven on the church after the persecution of Diocletian, he carefully avoided all mention of the Nicene synod, lest he should be obliged to describe the seditions of Bishops quarrelling among themselves. Because writers of history ought especially to be careful that their work concludes with some glorious event, as Dionysius Halicarnassus had long before intimated in his comparison of Herodotus and Thucydides. Now what event more illustrious could have been desired by Eusebius, than that repose which, after a most sanguinary persecution, had been restored to the Christians by Constantine; when, the persecutors being every where extinct, and Licinius himself at length removed, no fear remained of such evils as had been experienced? This epoch, therefore, rather than that of the Nicene council, afforded the most eligible limit to his Ecclesiastical History. For in that synod, the contentions seemed not so much appeased as renewed; and that not through any fault of the synod itself, but by the pertinacity of those who refused to acquiesce in the very salutary decrees of that venerable assembly.

Having said thus much relative to the life and writings of Eusebius, it remains to make some remarks in reference to the orthodoxy of his faith. Let not the reader, however, here expect from us a defence, nor even any opinion of our own, but rather the judgment of the church and of the ancient fathers concerning him. Wherefore certain points shall be here premised, as preliminary propositions, relying on which, we may arrive at the greater certainty relative to the faith of Eusebius. As the opinions of the ancients concerning Eusebius are various, since some have termed him a Catholic, others a heretic, others a διγλωττον, a person of a double tongue, or wavering faith, it is incumbent on us to inquire to which opinion we should chiefly assent. Of the law it is an invariable rule, to adopt, in doubtful cases, the more lenient opinion as the safer alternative. Besides, since all the westerns, St. Jerome excepted, have entertained honourable sentiments relative to Eusebius, and since the Gallican church has enrolled him in the catalogue of saints, it is undoubtedly better to assent to the judgment of our own [the western] fathers, than to that of the eastern schismatics. In short, whose authority ought to be more decisive in this matter than that of the bishops of Rome? But Galesius, in his work on the Two Natures, has recounted our Eusebius amongst the catholic writers, and has quoted two authorities out of his books. Pope Pelagius, too, terms him the most honourable amongst historians, and pronounces him to be free from every taint of heresy, notwithstanding he had highly eulogized the heretical Origen. Some, however, may say, that since the Easterns were better acquainted with Eusebius, a man of their own language, a preference should be given, in this case, to their judgment. Even amongst them, Ensebius does not want those, Socrates and Gelasius Cyzicenus| for example, who entertained a favourable opinion concerning him. But if the judgment of the Seventh Œcumenical Synod be opposed to any inclination in his favour, our answer is ready. The faith of Eusebius was not the subject of that synod’s debate, but the worship of images. In order to the subversion of which, when the opponents that had lately assembled in the imperial city had produced evidence out of Eusebius’s letter to Constantia, and laid the greatest stress thereon, the fathers of the Seventh Synod, to invalidate the authority of that evidence, exclaimed that Eusebius was an Arian. But this was done merely casually, from the impulse of the occasion, and hatred of the letter, not advisedly, or from a previous investigation of the charge. They produce some passages, it is true, from Eusebius, to insinuate that he was favourable to the Arian hypothesis; but they avoid all discrimination between what Eusebius wrote prior to the Nicene Council, and what he wrote afterwards, which, undoubtedly, ought to have been made as essential to a just decision relative to Eusebius’s faith. In short, nothing written by Eusebius before that synod is fairly chargeable, in this respect, against him. Eusebius’s letter to Alexander, containing his intercession with that prelate for Arius, was certainly written before that council. The affirmation, therefore, of the fathers of the Seventh Synod, notwithstanding it has the semblance of the highest authority, seems rather to have arisen from the prejudice than the mature judgment of the council. The Greeks may assume the liberty to think as they please concerning Eusebius, and to term him an Arian, or a favourer of that heresy; but who can patiently endure St. Jerome, who, not content with calling him heretic and Arian, frequently terms him the ringleader of that faction? Can he be justly termed a ringleader of the Arians, who, after the Nicene Council, always condemned their opinions? Let his books De Ecclesiasticâ Theologiâ be perused, which he wrote against Marcellus long after the Nicene Council; and we shall find, what we have affirmed, that he condemned those who asserted that the Son of God was made of things not existing, and that there was a time when he existed not. Athanasius, likewise, in his letter relative to the decrees of the Nicene Council, attests the same fact concerning Eusebius, in the following words: “In this, truly, he was unfortunate: that he might clear himself, however, of the imputation, he ever afterwards charged the Arians, when they said that the Son of God had not existed before he was begotten, with virtually denying, in this way, his existence before his incarnation.” With this testimony too, Eusebius was favoured by Athanasius, notwithstanding the personal differences between them. But St. Jerome, who had no cause of enmity against Eusebius, who had profited so liberally by his writings, who had translated his Chronological Canon, and his Book De Locis Hebraicis into Latin, notwithstanding, brands Eusebius with a calumny, which even his most malignant enemies never fastened on him. The reason of this we cannot conjecture, except it is, that St. Jerome, in consequence of his enmity to Origen, persisted in an unqualified persecution of all that maintained his opinions, particularly Eusebius.

On the other hand, we do not conceal the fact, that Eusebius, though he cannot be deservedly esteemed a ringleader of the Arian faction, yet after the Nicene Council, was perpetually conversant with the principals of that party, and, together with them, opposed the catholic bishops, Eustathius and Athanasius, the most strenuous advocates for the adoption of the term ὁμοούσιος. Though Eusebius always asserted the eternity of the Son of God, against the Arians, yet in his disapproval of that word he seems censurable. It is certain that he never made use of that term, either in his books against Marcellus, or in his orations against Sabellius. Nay, in his Second Book against Sabellius, he expressly declares, that since that word is not in the Scriptures, it is not satisfactory to him. On this occasion he speaks to the following effect: “As not inquiring into truths which admit of investigation is indolence, so prying into others, where the scrutiny is inexpedient, is audacity. Into what truths ought we then to search? Those which we find recorded in the Scriptures. But what Ave do not find recorded there, let us not search after. For had the knowledge of them been incumbent on us, the Holy Spirit would doubtless have placed them there.” Shortly after, he says: “Let us not hazard ourselves in such a risk, but speak safely; and let not anything that is written be blotted out.” And in the end of his oration, he thus expresses himself: “Speak what is written, and the strife will be abandoned.” In which passages, Eusebius, no doubt, alludes to the word ὁμοούσιος.

Finally, we now advert to the testimonies of the ancients concerning Eusebius. Here one thing is to be observed, namely, however various the opinions of men have been relative to the accuracy of the religious sentiments of Eusebius, all have unanimously esteemed him as a person of the most profound learning. To this Ave have to mention one solitary exception, Joseph Scaliger, who within the memory of our fathers, impelled by the current of temerity, and relish for vituperation, endeavoured to filch from Eusebius those literary honours which even his adversaries never dared to impugn. On Scaliger’s opinion, we had at first determined to bestow a more ample refutation; but this we shall defer, until more leisure on the one hand, or a more urgent claim on the part of the reader, on the other, shall again call our attention to the subject.

Support Site Improvements

Support Site Improvements